It is with great pleasure that I announce the latest open source release from Microsoft. This time it’s coming from Bing.

Before explaining what it is and how it works, I have to mention that nearly all of the work for actually getting this setup on GitHub and preparing it for public release was done by by Chip Locke [Twitter | Blog], one of our superstars.

What It Is

Microsoft.IO.RecyclableMemoryStream is a MemoryStream replacement that offers superior behavior for performance-critical systems. In particular it is optimized to do the following:

- Eliminate Large Object Heap allocations by using pooled buffers

- Incur far fewer gen 2 GCs, and spend far less time paused due to GC

- Avoid memory leaks by having a bounded pool size

- Avoid memory fragmentation

- Provide excellent debuggability

- Provide metrics for performance tracking

In my book Writing High-Performance .NET Code, I had this anecdote:

In one application that suffered from too many LOH allocations, we discovered that if we pooled a single type of object, we could eliminate 99% of all problems with the LOH. This was MemoryStream, which we used for serialization and transmitting bits over the network. The actual implementation is more complex than just keeping a queue of MemoryStream objects because of the need to avoid fragmentation, but conceptually, that is exactly what it is. Every time a MemoryStream object was disposed, it was put back in the pool for reuse.

-Writing High-Performance .NET Code, p. 65

The exact code that I’m talking about is what is being released.

How It Works

Here are some more details about the features:

- A drop-in replacement for System.IO.MemoryStream. It has exactly the same semantics, as close as possible.

- Rather than pooling the streams themselves, the underlying buffers are pooled. This allows you to use the simple Dispose pattern to release the buffers back to the pool, as well as detect invalid usage patterns (such as reusing a stream after it’s been disposed).

- Completely thread-safe. That is, the MemoryManager is thread safe. Streams themselves are inherently NOT thread safe.

- Each stream can be tagged with an identifying string that is used in logging. This can help you find bugs and memory leaks in your code relating to incorrect pool use.

- Debug features like recording the call stack of the stream allocation to track down pool leaks

- Maximum free pool size to handle spikes in usage without using too much memory.

- Flexible and adjustable limits to the pooling algorithm.

- Metrics tracking and events so that you can see the impact on the system.

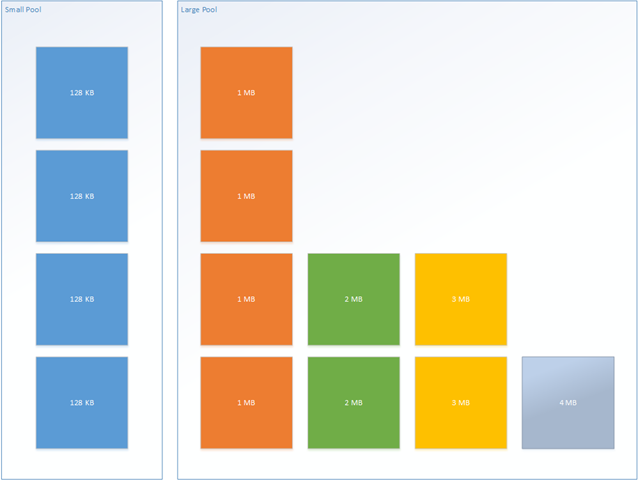

- Multiple internal pools: a default “small” buffer (default of 128 KB) and additional, “large” pools (default: in 1 MB chunks). The pools look kind of like this:

In normal operation, only the small pool is used. The stream abstracts away the use of multiple buffers for you. This makes the memory use extremely efficient (much better than MemoryStream’s default doubling of capacity).

The large pool is only used when you need a contiguous byte[] buffer, via a call to GetBuffer or (let’s hope not) ToArray. When this happens, the buffers belonging to the small pool are released and replaced with a single buffer at least as large as what was requested. The size of the objects in the large pool are completely configurable, but if a buffer greater than the maximum size is requested then one will be created (it just won’t be pooled upon Dispose).

Examples

You can jump right in with no fuss by just doing a simple replacement of MemoryStream with something like this:

var sourceBuffer = new byte[]{0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7};

var manager = new RecyclableMemoryStreamManager();

using (var stream = manager.GetStream())

{

stream.Write(sourceBuffer, 0, sourceBuffer.Length);

}

Note that RecyclableMemoryStreamManager should be declared once and it will live for the entire process–this is the pool. It is perfectly fine to use multiple pools if you desire.

To facilitate easier debugging, you can optionally provide a string tag, which serves as a human-readable identifier for the stream. In practice, I’ve usually used something like “ClassName.MethodName” for this, but it can be whatever you want. Each stream also has a GUID to provide absolute identity if needed, but the tag is usually sufficient.

using (var stream = manager.GetStream("Program.Main"))

{

stream.Write(sourceBuffer, 0, sourceBuffer.Length);

}

You can also provide an existing buffer. It’s important to note that this buffer will be copied into the pooled buffer:

var stream = manager.GetStream("Program.Main", sourceBuffer,

0, sourceBuffer.Length);

You can also change the parameters of the pool itself:

int blockSize = 1024;

int largeBufferMultiple = 1024 * 1024;

int maxBufferSize = 16 * largeBufferMultiple;

var manager = new RecyclableMemoryStreamManager(blockSize,

largeBufferMultiple,

maxBufferSize);

manager.GenerateCallStacks = true;

manager.AggressiveBufferReturn = true;

manager.MaximumFreeLargePoolBytes = maxBufferSize * 4;

manager.MaximumFreeSmallPoolBytes = 100 * blockSize;

Is this library for everybody? No, definitely not. This library was designed with some specific performance characteristics in mind. Most applications probably don’t need those. However, if they do, then this library can absolutely help reduce the impact of GC on your software.

Let us know what you think! If you find bugs or want to improve it in some way, then dive right into the code on GitHub.

Links

- Microsoft.IO.RecyclableMemoryStream on GitHub

- NuGet package

- Writing High-Performance .NET Code [Book that will explain the situations in which you may need something like this in a high amount of detail]